Book Reviews: It is all about education. Whether you collect books or autographs or both, the educated collector is the savvy collector. Just ask Bill Butts. Every year a stream of reference works, how-tos, exhibition catalogs, bibliographies, and memoirs useful to collectors come on the market. Few receive scant attention in the media. Since 1992 William “Bill” Butts has reviewed between 3 and 6 new books in every issue of Manuscripts.

One Really Bad Egg and a Visit to Calling Cards

William Butts

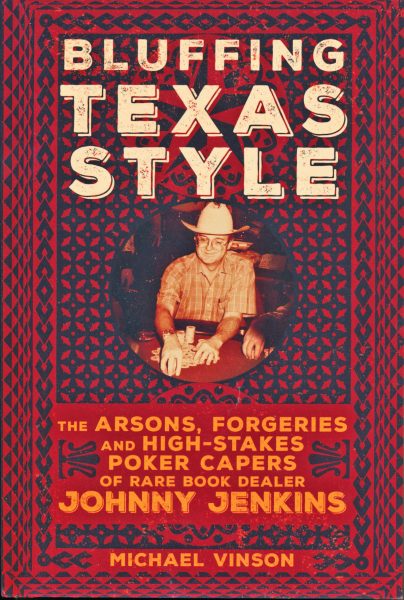

VINSON, Michael. Bluffing Texas Style: The Arsons, Forgeries, and High-Stakes Poker Capers of Rare Book Dealer Johnny Jenkins. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2020. 8vo. x, 236pp. Illustrations. Hardbound $45.00, softbound $21.95.

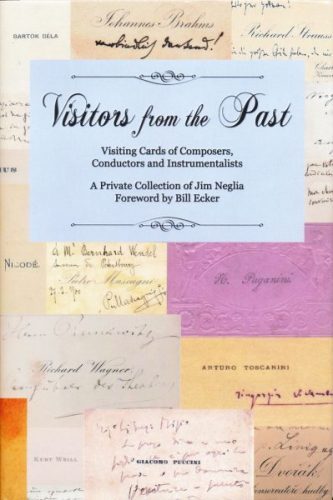

NEGLIA, Jim. Visitors from the Past: Visiting Cards of Composers, Conductors and Instrumentalists. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2020. Small 4to. Hardbound, dust jacket. 244pp. Illustrations. Hardbound $29.99, softbound $24.99.

Bluffing Texas Style by Michael Vinson

If rare book and historic document dealers were eggs, you’ve got your good eggs and your bad eggs. (Like most analogies, it breaks down if you scrutinize closely – what about your hard-boiled types?) The problem with a really bad egg like Johnny Jenkins – despicably corrupt and a disgrace to the profession – is that this tale is so outrageous you can’t make it up, it makes for a great read, and appeals to a far broader audience than a the story of a reputable dealer. Rotten eggs cause far more damage than they warrant in a worthy profession that’s long centered on trust, integrity, and good faith. In this dealer’s experience, rare book dealers and historical document dealers are the salt-of-the-earth types, savvy but honorable business people. Sure, we’re as human as any other calling and a stinker does occasionally fall in our midst – cream and bastards both rise to the top. Fortunately, the crooked dealer whose escapades get broad coverage are the rare exception.

In 1989 I had just entered the world of historical documents and rare books on a professional level when a .38 Special bullet entered at the back and exited near the front of Texas book dealer John H. Jenkins’s head, so our paths never crossed. “Years later,” writes author/bookseller Michael Vinson, “most rare book dealers of a certain age” – the generation ahead of me – “could recall where they had been when they heard the news of the violent finish to Jenkins’s flamboyant life” – an observation usually applied to the violent death of another flamboyant John in Texas a quarter century earlier. As for me, I was learning the ropes from another flamboyant bookseller on floor fifty-something of Chicago’s John Hancock skyscraper at the time. I recall him describing his business with a grin as “the highest bookstore in the world both in location and price”.

Among the shelves full of books-about-books I devoured back then was Jenkins’s 1976 Audubon and Other Capers: Confessions of a Texas Bookmaker (which I swallowed hook, line and sinker), Calvin Trillin’s lengthy 1989 New Yorker profile, scads of book trade articles and a few years later W. Thomas Taylor’s compelling 1991 Texfake: An Account of the Theft and Forgery of Early Texas Documents (reviewed in the Fall 1992 issue of this column).

Having reviewed Vinson’s page-turner Edward Eberstadt & Sons: Rare Booksellers of Western Americana in the Fall 2016 issue of this column, I saddled up for a gut-wrenching bronco-buster of a read and am not disappointed. In Bluffing Texas Style Vinson unearths a never-ending string of lies and deceptions, many reported here for the first time, and connects the dots into a coherent picture. It’s as riveting as it is horrifying and dispiriting. One passage that sticks in my mind is Vinson’s speculation on the psychological basis for Jenkins’ insane need to be looked up to:

Why did he have an insatiable need to exaggerate and embroider nearly every story?… Jenkins exaggerated stories about his achievements for the same reasons that he drove flashy cars: because he wanted to be admired. The American Psychological Association defines such individuals as suffering from histrionic personality disorder. The symptoms include excessive attention seeking and deep need of approval from others. These colorful persons have lively and enthusiastic personalities that are often accompanied by volatile emotions and extreme behaviors. They have a constant craving for stimulation and often fail to see their own personal situation realistically. They become bored easily, and when presented with difficulties they prefer to withdraw rather than face them. Anyone so afflicted will never have a car expensive enough or a story large enough to compensate. Every new purchase or tale of derring-do is only a temporary salve for that person’s profound lack of self-worth….

Vinson repeatedly drops samples of Jenkins’ inability to tell the truth about anything. Every kernel of truth (if kernel there be) became fodder for wild stretchers. The $50 weekly line of credit his father opened for a 12-year-old Jenkins (to fund rolls of nickels, dime and quarters he searched for collectible coins) became five thousand dollars in his retelling… his 1962 around-the-world honeymoon cost a huge $4000 but he “bragged that it had cost $35,000”… the rustic cabin his parents gifted him for high school graduation he claimed “he bought… with the royalties from his first book” – on and on. Vinson spells out dozens of outlandish mistruths that Jenkins spun regarding just about every facet of his life, major and minor.

Vinson’s investigation nicely fills out our image of the short, cigar-chomping, tall-tale-telling Texan in alligator cowboy boots and white tall-sided Stetson who yearned to be larger than life. The fuller this portrait becomes, the more his inflated lies and criminal business dealings are popped and Jenkins deflates and crumples like a rootin’-tootin’ Yosemite Sam balloon pricked full of holes in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day.

Among the many smoking guns Vinson discovered in the Jenkins Papers at the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University and elsewhere is a letter from one partner in crime which proves that Jenkins was stealing rare books and documents his entire adult life, from his first job at the Texas state archives while a college student. The wunderkind of antiquarian bookselling did everything oversize and before long established a rare book and publishing shop in Austin, partnered in an art gallery and an antique shop, acquired a bindery and dove into projects like an empire builder on steroids. The press loved the colorful, Rolls Royce-driving young braggadocio.

Shady dealing opportunities abounded and Jenkins took advantage of them all. His first catalogue was devoted entirely to material about the recently assassinated President Kennedy and featured a number of JFK letters he purchased as secretarially signed and foisted on the unwary as authentic.

Most notable among Jenkins’ early dealings, he attracted wildly erratic drug-addled trust fund baby Dorman David, a Houston bookseller who “gyrated between bouts of existential anxiety and a vaulting conviction of his own native genius.” Turns out David also printed forgeries of fabulously rare printed revolutionary Texas documents such as the one-page Texas Declaration of Independence on reproduction antique paper purchased in England (500 pounds’ worth!). These he often sold with a wink and a nudge to Jenkins. Later he orchestrated the theft on a massive scale of rare books and documents from a network of thieves who visited county archives across the country. Jenkins and David each seemed aware of the other’s illicit activities in those salad days and they bought and traded between themselves frequently and extravagantly.

So many, so varied and so self-publicized were Jenkins exploits – read “crimes” – that I’ll highlight just a couple of Vinson’s revelations to give you the flavor of Bluffing Texas Style. How’s this for two bubble bursters: The real goal of Jenkins’ self-published Audubon and Other Capers was to give him the legitimacy to earn election into the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA) – but more importantly, his heroic tale of arranging a sting operation with the FBI in 1970 to recover a horde of Audubon bird plates stolen from Union College in New York only came the way of “an out-of-the-way bookseller in Austin, Texas” because “Jenkins… had done a deal the previous year with the ringleader of the Audubon thefts”! As for the purchase of the enormous and fabulously rich inventory of East coast dealer Edward Eberstadt and Sons in 1975, which garnished Jenkins worldwide press coverage and the profits from which could have kept the Jenkins Company in excellent fiscal health for the rest of his life if managed properly, instead became the enabler that fueled an escalating string of crimes. Vinson’s elaboration of Jenkins’ intricate financing of this $2.5 million once-in-a-lifetime deal will cross your eyes, but is quite engrossing.

Jenkins’ lifelong love of gambling grew to a debilitating addiction and led to his ultimate undoing in the 1980s as he spent upwards of two months per year and massive amounts of money in Las Vegas and other gambling meccas feeding his craving. Occasionally he won nice-sized pots and he parlayed press interest in the bookselling poker player known as “Austin Squatty” (he sat cross-legged on his chair to appear taller), but the buy-ins were often ruinous and losses far exceeded wins. Vinson wisely latches onto the perverse adrenalin rush Jenkins got from gambling as explanation for his bizarrely impulsive behavior. “Jenkins played professional poker the same way he conducted his rare book business,” Vinson conjectures. “…he was far better at publicizing that he played than he was at actually winning tournaments.”

When he substituted “a beautiful copy of Sam Houston Displayed – a rare pamphlet printed in 1837 he had sold to [best customer] French… with a $35 reprint,” Vinson believes this reflects “his desire for an additional risk in the transaction. He substituted forgeries and inferior copies to sophisticated collectors and scholars just as readily as he did to a beginning collector like French. The risk of a daring and unethical impulse seemed to drive him more than anything else.” Elsewhere, Vinson notes how Jenkins “convinced himself that the difference between authentic printed documents and fake ones didn’t matter as long as the customer believed the fakes were real. Or perhaps it was Jenkins’s experience with poker, where an unrevealed card in the hand could be whatever he could bluff someone into believing.”

Fascinating are the disparities of opinion regarding Jenkins. Fellow Austin bookseller Dick Bosse “thought Jenkins was probably the most creative rare book dealer of his century,” while another rather naive source offered this praise:

Jenkins handled and placed great works and archives of literature related to such well-known writers as Jane Austen, Herman Melville, and Mark Twain. He appraised over seven thousand IRS donations of rare books and manuscripts. He imagined and pioneered categories unknown to other rare book cataloguers in the 1970s, including catalogue listings on JFK, NASA and space exploration, anti-Vietnam protests, and even the civil rights movement, long before social history was a fashionable academic trend.

William Reese, on the other hand, the universally respected dean of Americana dealers, saw clearly through Jenkins’ bluster and viewed him as an enterprising if bumbling bibliopole. (You won’t know whether to laugh or cry when Vinson shows Jenkins taking the rare 3-volume true first edition of Moby Dick, bound in original blue cloth with tan cloth spines, and assumes the spines are faded: “he fixed the ‘problem’ himself by coloring the spines to match the boards with a blue sharpie… Jenkins never lost his proclivity for finding solutions to nonexistent problems.” Or the time when he sold the University of Texas his half, 163 pages, of a 326-page Albert Einstein archive he’d co-owned with another dealer, but represented it as the complete 326-page archive. How did he accomplish this trick? “Easy… He just had his staff tear each of the 163 Einstein manuscripts in half… so that there were now 326 manuscripts, just as described in the auction catalogue.”)

Writes Vinson, “Reese did consider him not a particularly brilliant or even smart rare book seller. By this Reese did not mean that Jenkins did not ever purchase valuable books in fields such as Texana; he simply meant that Jenkins was much more comfortable buying scarce, not-so-scarce, and even common books to build a collection that could be foisted on some new unsuspecting collector.”

Given what we now know, it’ a black eye (more like a huge purple and green shiner) for the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America that in 1972 Jenkins – who’d been denied admission in 1970 – finally finagled his way into admission through deception. It was a dark and stormy night when he advanced to their board of governors in 1973. The greatest stain came in 1980 when he was elected to a two-year term as president. Ironically, in 1981 under their auspices he authored the pamphlet Rare Book and Manuscript Thefts: A Security System for Libraries, Booksellers, and Collectors. The ultimate slap is that near the end of his life, as his pyramid crumbled, he served as their security officer and FBI liaison. We all know that the internet has proven a boon for all manner of thievery and deception – but let’s also hope that the internet age, the ability to keep buyers and sellers of rare books and documents and presence of forgeries instantly informed and up to date, will thwart and expose future Jenkins types before they can flourish.

I don’t envy any writer the task of dissecting a life as messy and convoluted as that of Johnny Jenkins, a master of obfuscating his misdeeds. Investigative reporting is arduous enough with subjects who are straight shooters and at least strive for some semblance of the truth in their dealings and record-keeping. With a subject as secretive and deceitful as Jenkins, whose every utterance cannot be taken at face value, many writers would throw up their hands in despair. But Vinson presses on and largely succeeds in untying the untangleable.

Bluffing Texas Style shows off his perseverance and sleuthing to devastating effect. Sure, the chronology may seem a bit hazy at times, some aspects of his life in need of fleshing out, but overall this engaging exposé neatly lays out what happens when a pathological liar completely lacking moral compass lays waste to a profession so reliant on ethical behavior and respect for history.

Stetsons off to Michael Vinson!

Visitors from the Past by Jim Neglia

Collectors of autographs in the broad music field, rejoice!

Another weapon has been added to the rather slim arsenal of reference works at your disposal: Jim Neglia’s handy Visitors from the Past: Visiting Cards of Composers, Conductors and Instrumentalists.

A standard signature exemplar reference for decades has been several slim volumes compiled by Columbia Artists Management general manager F.C. Schang: Visiting Cards of Celebrities, Visiting Cards of Prima Donnas, Visiting Cards of Violinists, Visiting Cards of Pianists and Visiting Cards of Painters, all published between 1971 and 1983 and long out of print. Another standard reference has been J.B. Muns’ pamphlet Musical Autographs, first published in 1989 with three supplements published in 1991, 1994 and 1996 – the first out of print but the supplements still available from Muns.

Visitors from the Past continues the format and tradition of Schang’s volumes and avoids duplicating their subjects. Dealer Bill Ecker of Harmonie Autographs provides an able foreword, explaining the history of these quaint relics:

…printed and engraved business cards did not make the scene in the West until the 17th century, and initially, they were a social implement, rather than a business tool. The social cards were called visiting cards, or in the more acceptable French “cartes de visites.” Their purpose was to announce your presence in an aristocratic or wealthy home. One would hand the printed card with your name to the servant who greeted you at the door, and the card announcing your presence was brought to the person you were visiting in another room of the home or office…. If the person visited was not at home, many would leave a short message on their card. If the person was unknown to the visitor, they might write a note of greeting, hoping they would be received. Hence, many of the cards became autographed….

While Ecker notes Frederic Schang’s “collection of performing arts visiting cards in four volumes,” it should be noted that after what he calls “Schang’s final volume, Visiting Cards of Pianists… in 1979” Schang brought out a fifth Visiting Card collection in 1983 — Visiting Cards of Painters. Which begs the question: Could one argue that paintings and artwork are performing arts? Art lovers, after all, do maintain that art speaks to them!

Neglia recalls in his introduction how his autograph collection began in 1995 in one of my favorite old haunts – the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna’s ancient, densely-packed first district. There he ran across an autograph shop and held “an actual letter that Johannes Brahms wrote in 1872. From that day forward, I was under the spell of collecting these treasures for my consumption…. I have been collecting autographs and ephemera on composers for the better part of 25 years, and my collecting has grown exponentially. At the time of writing, my collection exceeds 700 pieces.”

113 figures populate Visitors from the Past, ranging from household-name famous (Igor Stravinsky, Johann Strauss, Pablo Casals, Arturo Toscanini, Maurice Ravel, Richard Wagner, Cole Porter, Johannes Brahms, many others) to dozens less well known except to serious classical music enthusiasts. Most are 19th century figures, though two were born in the late 18th century and five born in the early 20th century.

Each two-pager consists of a portrait and several-sentence biographical writeup at left and an enlargement of the person’s calling card (verso too if written upon) at right. A dual contents page lists all 113 alphabetically (Daniel Auber through Charles Ziehrer) and chronologically by birth (Auber in 1782 through Henryk Szeryng in 1918) – this last determines their order of appearance. The purpose baffles me, although fanning the pages slowly like a flip book offers a quick survey in the development of calling card design. Lacy italic typefaces dominate, with the occasional Roman and a pseudo-Gothic thrown in, while simpler modern typefaces appear in the mid-20th century cards.

Visitors from the Past is a fine source of signature and handwriting exemplars from this broad range of music figures – many of whom aren’t easy to locate in the existing literature. Only a few calling cards bear no writing whatsoever, the vast majority are signed (usually with salutation or brief greeting), and four are lovely AMuQsS (Hector Berlioz, Antonio Carlos Gomes, Victor Herbert and George Szell).

A surprising number bear lengthy, almost letter-length messages. It amazes how much those with a diminutive hand could cram onto one or both sides of a card roughly 4” X 3” – Jules Massenet, Henri Marteau, Hans von Bulow, Richard Strauss, Hugo Heermann, and Charles Gounod being notables examples of what’s practically a miniature ALS or ANS. Below each calling card image is a full translation (French, Czech, Italian, Polish, German, Norwegian and Fraktur). Amusingly, two of the very few English inscriptions bear transcription inaccuracies: Percy Grainger’s inked “from” is shown as ellipses and Jozef Michal Poniatowski’s inked “I just succeeded in getting this one copy for you, for the train! with Kindest regards” is mistranscribed as “I just […] getting this, the copy for you, for the train! With a hundred regards….” Quite minor flaws, these.

As useful as Neglia’s Visitors from the Past is, it is not without issues. While the thumbnail biographies of his subjects read well, for some reason his introduction occasionally reads flat and even clunky. His grasp of autograph collecting terminology seems a bit faulty. He writes, “There were acronyms such as ANS which meant, Autograph Note Signed, ALS, SP, or AMusQ representing Autograph Letter Signed, Signed Picture, and Autograph Musical Quote; the quotes were handwritten music quotes from selections that the composer chose to include in their signature.”

Awkwardness aside, an “SP” is properly termed a “PS,” which means “Photograph Signed,” not “Signed Picture.” An “AMusQ” is properly termed an “AMuQS,” which means “Autograph Musical Quotation Signed,” not “Autograph Musical Quote.” (There is such a thing as an “AMuQ,” meaning an unsigned “Autograph Musical Quotation.”) The Manuscript Society published a useful terminology pamphlet quite a few years ago which establishes a proper terminology from the haphazard variants one used to see and has become the standard, accepted reference. Physically, Visitors from the Past is sturdy and attractive, though I’m not fond of the slightly translucent, weakly sized (the coating that renders paper non-absorbent) stock that makes the pages prone to faint waviness. All trivial quibbles.

Visitors from the Past: Visiting Cards of Composers, Conductors and Instrumentalists represents a worthy sequel to F.C. Schang’s long-ago calling card surveys. For those lacking these Schang titles, I suggest get thee online and piece together a set. Jim Neglia’s successor to these is a must-have for serious calling card and classical music autograph collectors.

Book Reviews by William Butts: In every issue of the society journal, Manuscripts. Get your issue of Manuscripts by joining the Manuscript Society

Leave A Comment