Lost: Lessons from the Carnegie Library Theft

Michael J. Dabrishus

“They are only sorry that we discovered what they did,” said Mary Frances Cooper, director of Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. She was speaking as a witness at the June [2020] sentencing of Gregory Priore and John Schulman. The sentencing testimony went on for two days at the Allegheny County Courthouse in downtown Pittsburgh. The thefts from the library went on for more than 20 years.

Stolen Treasures

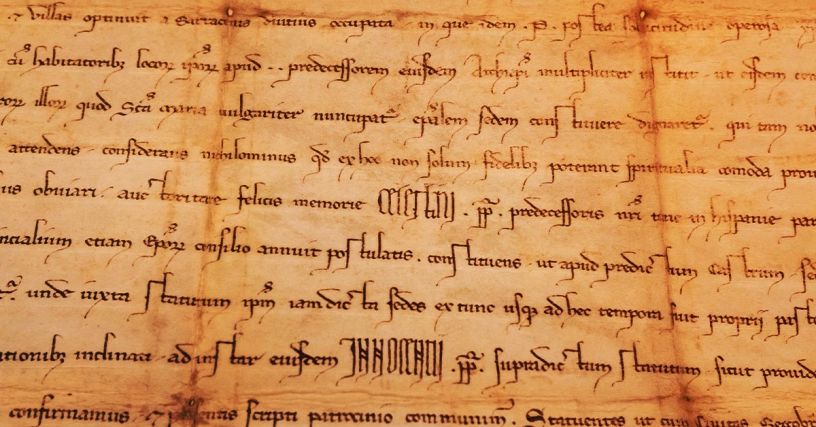

In that time, Priore, a library employee, stole more than 300 rare items. Schulman, a dealer and co-owner of Caliban Book Shop, just a couple of blocks from the library, knowingly sold the items. Both entered guilty pleas. Replacement value for the missing items exceeds $8 million. Even that figure is considered low, as many of the items, like manuscripts, simply can’t be replaced.

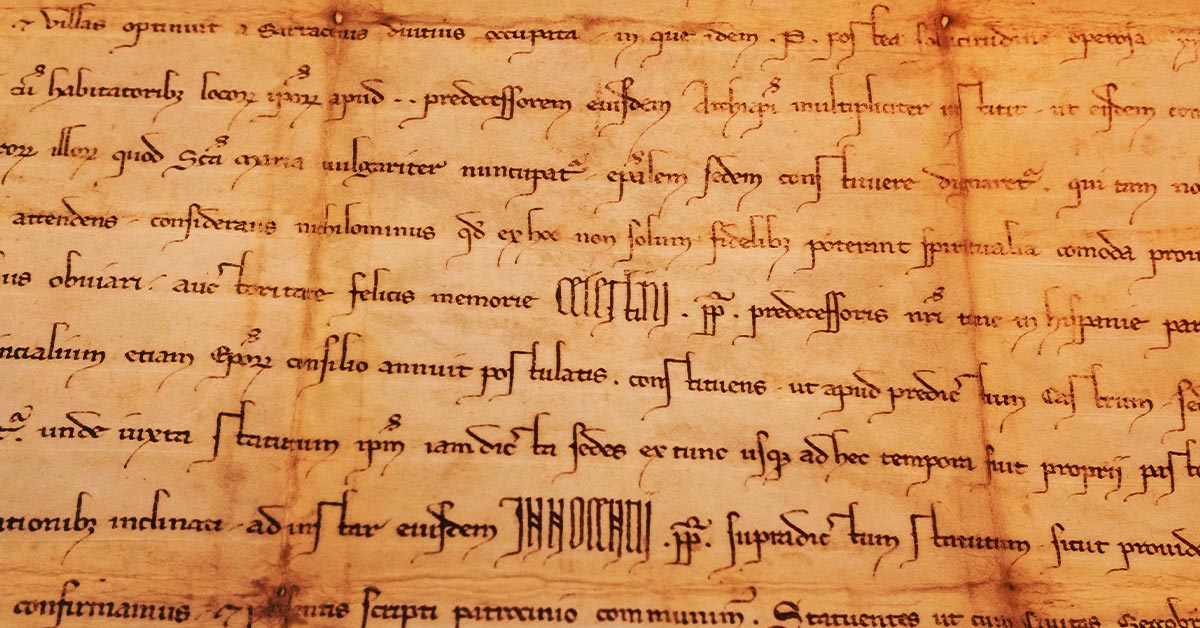

Breeches Bible, 1615, recovered through the FBI’s Art Crime Team. FBI Pittsburgh photo.

Among the missing are treasures like Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ naturalis principia mathematica (1687) and maps from Ptolemy’s Geographica (1548). Gone are hand-colored plates from McKenney and Hall’s History of the Indian Tribes of North America (1836 and 1844), as well as prints and plates from Edward S. Curtis’s monumental work on Native Americans. A copy of Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Eighty Years and More (1898) likewise vanished. This is just a sampling. A full inventory of the losses appears on the Manuscript Society’s website at https://manuscript.org/2018/03/314-rare-items-stolen-from-carnegie-library.

Many people expressed astonishment at the magnitude of the theft. How could the Priore and Schulman have gotten away with it? And for so long!

Consider the culprits. Priore worked for more than 30 years in the library. He was director of the Oliver Room, in essence the library’s special collections department, until he was found out and fired in June 2017. Schulman has owned his bookshop since 1991. He was a member of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America and served on its Ethics & Standards Committee. He appraised collections for individuals and institutions alike, and his appearances on Antiques Roadshow brought him into the homes of PBS viewers across the United States. Both were known and trusted.

Insider theft in libraries and archives is difficult to prevent. Employees have access to rare items. True, those materials are held in secure physical spaces, some with 24/7 surveillance systems and vaults. Other measures are in place too. But the human element of personnel centers on trust—a key factor that led to Carnegie Library’s losses.

Warning Signs

There were warning signs with materials that Schulman was selling. The most obvious were Carnegie Library ownership marks. Libraries routinely dispose of duplicate books, especially when they receive a copy in better physical condition. Indeed, it’s not uncommon to see “ex-library copy” in descriptions of books for sale. The vast majority of such items are legitimately deaccessioned and usually not worth thousands of dollars.

Of the books in the Carnegie case, many bear Oliver Room bookplates, usually on the inside front cover. On many that Schulman sold, “Withdrawn from library” was stamped across the plate. Interestingly, a hand stamp bearing those exact words was found at Schulman’s warehouse after a search warrant was issued. (So were rare prints and maps, part of the stolen materials.)

Schulman claimed, at one point, that Priore was authorized to sell rare materials. At no time was that actually the case. Also, payment for such materials goes through proper library channels, normally not through an individual, and never in cash. According to a Pittsburgh Post-Gazette report, Priore received checks from Schulman’s shop and made substantial cash deposits. Indeed, had Schulman simply called the director’s office, he would have learned the items he was buying were stolen.

Justice Served?

At the close of the second day of the hearing, Judge Alexander P. Bicket announced the sentences. Schulman received four years of house arrest and 12 years of probation. In addition he had to pay $55,731 in restitution to those who bought stolen items that were recovered. Priore was sentenced to three years of house arrest and 12 years of probation. Bicket noted, “Without a doubt, were it not for the pandemic, the sentencing for both of these defendants would be significantly more impactful.”

A great many people were not happy with the verdict. Far too often, convicted thieves of rare historical materials “get off light.” Carole Kamin, a friend of the late John R. Oliver, for whom the special collections room at Carnegie Library was named, wrote in a letter to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette:

“The sentencing judge reportedly stated that COVID-19 was a factor weighing against imposition of incarceration.… He did not explain why prison terms could not have been served in isolation or begun at some later date. The end result is long-term damage to the library and a limited period of inconvenience to the convicted criminals. Is this justice?”