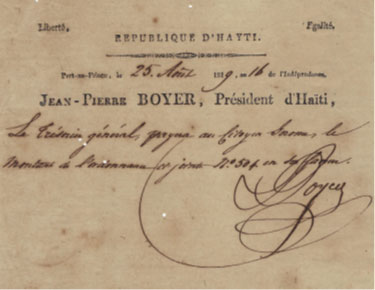

Document signed by Jean-Pierre Boyer, president of Haiti from 1818 to 1843

Haitian Presidential Material

Stuart Embury, MD

My Passion

One of my passions in life is medical volunteer work in Haiti. I have gone to Haiti each of the last 40 years, leading teams of volunteers. Along the way, I became fascinated with the history of Haiti. That fascination became intertwined with my interest in manuscripts.

As you can imagine, Haitian material is somewhat difficult to find. Part of my collection involves Haitian presidential material. Among these are letters and documents by Toussaint L’Ouverture, Henri Christophe, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Alexandre Petion, Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier, and Jean Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. I have a nice document by Jean-Pierre Boyer, who was a very early president of Haiti.

I have a smattering of other documents, including a bill of sale, for a slave woman and her 10-year-old son, dated 1777. Translating this very fragile French document is on my to-do list. This will give me a project I can look forward to when I move into the nursing home!

In the 1700s, Haiti was known as the “Pearl of the Antilles,” the richest of France’s many colonies. In 1791 the slaves began a series of rebellions spearheaded by the Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture (1743–1803).

History

Toussaint stated, “I was born a slave, but nature gave me the soul of a free man.” He was attending a meeting under a flag of truce with the French when he was tricked and captured, and sent to prison in France, where he died a broken man in 1803. I often wonder what the country of Haiti would be today if Napoleon had formed an alliance and collaborated with Toussaint.

Toussaint was a fascinating individual, and I dreamed of owning a document signed by him. My dream was realized when I received a catalog from the autograph dealer Robert Batchelder. He offered a Toussaint document for sale. (In the same catalog, he extended an invitation to join the Manuscript Society, which I did. I was doubly blessed with that catalog!)

Collecting

Batchelder had an unusual treasure trove of Haitian documents, and I bought most of them. A few years later, I was looking at the itinerary for the Manuscript Society’s 2001 annual meeting in New York. I hadn’t even vaguely considered attending the meeting, but the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, one of the venues on the itinerary, promised an exhibition of Haitian material. I immediately snapped to attention, called my friend Wayne Quincy, and along with our wives, we attended our first meeting.

During the attempt by France to reestablish control of over Haiti in 1802, Napoleon sent his brother-in-law, General Charles Emanuel LeClerc, as commander of the 20,000-strong French invasion force. I secured a LeClerc letter and then added a letter of General Rochambeau, the second in command. The slaves eventually prevailed in 1804, and Haiti became the first black republic.

I’m still looking for a letter by LeClerc’s wife, Pauline Bonaparte. She left Haiti after he died and married Prince Camillo Borghese, one of the richest men in Italy. If you know where I might find such a letter, you can reach me through executivedirector@manuscript.org.

Stuart Embury is a family doctor who lives in Holdrege, Nebraska, but his work has taken him halfway around the world. Dr. Embury chairs the Manuscript Society’s Honors Committee. He and his wife, Lynn, are familiar faces at the society’s annual meetings. A version of this story previously appeared in Cornhusker Family Physician.

Become a member of the Manuscript Society. Share your collecting passion!

Leave A Comment