In the first of a new series spotlighting long time members of the Society, society Vice President, Allen Ottens interviews member Robert Snyder of Cohasco, Inc. Cohasco. Inc. is located in Yonkers, New York. Robert Snyder is a dealer in and auctioneer of historical documents, manuscripts, books, antiquarian materials, and collectibles.

In what areas does Cohasco specialize?

We’ve always been generalists with broad interests. Recent offerings included a Sumerian clay tablet ca. 1500 BC, medieval manuscripts, and mid-20th century material.

How long has Cohasco been in business? What got you started?

Founder Phil Snyder got his start in the business in the 1930s. As a teen, he’d frequent the hundreds of antique, curio, stamp, and coin shops in the New York City area, placing items on consignment. After serving in World War II, Phil began the current firm, in 1946. Now in our 71st year, we look forward to hitting 100.

My own collecting genes didn’t require much encouragement. I’d write to politicians, world leaders, scientists, and writers. In my early days, most of them saw their mail and not only supplied their autograph but often wrote a letter answering my question about their career, life, or philosophy.

What trends do you see in the collecting field?

Divining fortunes from tarot cards is easier than forecasting collecting trends. Specialties that seem as if they would be driven to popularity by major anniversaries and public awareness sometimes don’t sparkle. The lengthy Civil War sesquicentennial, for example, certainly didn’t hurt, but the influx of new collectors was more like a trickle. Happily, the public seems perpetually entranced by manuscripts and all the allied items collectors and institutions seek. The direction of our field is, naturally, limited by the budgets of new prospects and, more importantly, by their comprehension of what the items are.

Forecasting areas of future interest in manuscripts is made more difficult because it diverges from some other fields of collecting, such as antique automobiles. In those areas, it is accepted wisdom that many collectors seek items they remember from their youth or from periods they enjoyed. This thinking fails, of course, to explain why manuscript collectors assiduously gather Civil War, Revolutionary War, or medieval material.

What was the most unusual item you handled?

Many items have been unforgettable (and seeing them go equally regrettable!), but one recent item certainly fills the bill: a manuscript with the earliest appearance of the name “America” we’ve ever seen (albeit in Latinized form). Dateable to about 1230, it is the cover of an account book of “Lord Aymericus,” “defender of the people.” The book cover, and its accompanying manuscript leaf, are likely the only surviving artifacts of this obscure Knight of Bologna. Certainly, he had no inkling of what lay across the ocean, but the conversational attraction is beguiling.

Did you uncover any surprising finds?

Years ago, I placed a want ad for automotive history items, one of my personal interests. It elicited a call from someone who cleaned out houses. In this case, the home had belonged to J. Frank Duryea, one of the brothers who built America’s first “mass-produced” automobile (13 were made). The caller had been intrigued by some papers in the long-dormant garage.

What he’d found were the original manuscript drawings, with Duryea’s handwritten technical annotations, of the first and second prototypes of the motor for this groundbreaking vehicle. Not fully grasping their importance, the house cleaner dutifully observed that the pencil drawings could be darkened nicely, if I’d like him to trace over them with a magic marker. I declined the offer—but ecstatically purchased the items.

What is your advice to collectors, novice or experienced?

The literature of our hobby is filled with splendid advice to collectors. To this, I’d add my own raison: Long ago, supermarkets sold encyclopedias for young readers. These were slender works, priced so a parent wouldn’t balk at the cost. Filled with artwork, the content was compelling to an 8-year-old. The illustrations in the “M” volume really communicated to me. There, framing the lengthy entry on “Medieval,” were scenes of a street somewhere in Western Europe a millennium ago, with people in period garb, making their way over the cobblestones, past doorways of the buildings, all with their own stories and secrets.

Years later, when I saw Mary Benjamin’s concise listing for a fragment of a French manuscript of 1283, it stirred my memory of the pages in that supermarket encyclopedia. That initial acquisition led to a lifelong fascination with medieval manuscripts. So my advice to collectors is to watch for that spark, the intuitive voice within urging you to buy something.

What area of collecting is underappreciated or neglected?

First, few areas have become saturated. Consider the never-ending procession of books and articles on the Civil War, World War II, and many other epochs of history. There is always a new discovery awaiting the inquisitive collector. Areas that, until the last few years, have been often underpriced or under-appreciated include some colonial and Revolutionary War (other than blue-chip) material, and the “other” wars—the War of 1812, Mexican, Indian, and Spanish-American Wars.

It seems that some areas have long been backwaters, often sought only by the eclectic collector or sub-specialist. These areas present opportunities for collectors seeking reduced competition and reduced prices: local history; science and technology (other than the obvious standout figures); and association material, which, once gathered, can have historical, display, and monetary values greater than the sum of its parts.

Unless a collector is paying uncomfortably high prices for material, specializing in oddball fields should not be a deterrence. I’m reminded of the man who was collecting pre-1915 motorcycle literature and trade catalogues when he had the field nearly to himself. People at shows would literally laugh at him, ridiculing his foolishness. By the time he had a custom-designed, walk-in safe installed, he estimated his collection of “worthless” material to be in seven figures.

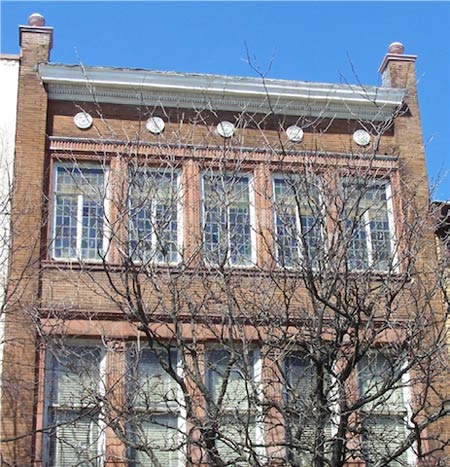

Even Cohasco’s home has historical interest.

The Cohasco Building was completed in 1857. During the Civil War, it housed Confederate prisoners in transit. The building served three police departments in succession and is considered the NYPD’s oldest surviving structure. Proprietor Bob Snyder quips that if he’d resist exploring the building’s historical rabbit holes, Cohasco could turn out several more catalogues a year.

Leave A Comment